Domestic water supply applications of Polypropylene (PPR) have been commercialized largely under the Aquatherm trade name and manufactured in Germany. After a period of reportedly reliable performance in Europe, Aquatherm began to market the product in Australia, Canada, the US, and elsewhere. Recently a string failures started to appear; first in Australia and now increasingly in the US.

Domestic water supply applications of Polypropylene (PPR) have been commercialized largely under the Aquatherm trade name and manufactured in Germany. After a period of reportedly reliable performance in Europe, Aquatherm began to market the product in Australia, Canada, the US, and elsewhere. Recently a string failures started to appear; first in Australia and now increasingly in the US.

After fire, water damage is the most expensive peril that a building owner may face. Many of these are winding up in the courts in what looks like the three-way shoot out at the end of the Clint Eastwood movie, The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly. The contractor is pointing at the manufacturer who in turn is pointing back at the owner/operator who is pointing alternately at the contractor and the manufacturer.

For the record, I like PPR for many reasons, but there appears to be 3 main vulnerabilities with PPR: the manner in which it is clamped, the temperature of the water, and the water chemistry – specifically the presence of copper ions. I call it the witches brew. If all three vulnerabilities are present, then the likelihood of failure is very high. If only one (or maybe two) of the vulnerabilities are present, the likelihood of failure seems substantially lower.

For the record, I like PPR for many reasons, but there appears to be 3 main vulnerabilities with PPR: the manner in which it is clamped, the temperature of the water, and the water chemistry – specifically the presence of copper ions. I call it the witches brew. If all three vulnerabilities are present, then the likelihood of failure is very high. If only one (or maybe two) of the vulnerabilities are present, the likelihood of failure seems substantially lower.

The problem is that each of the litigating parties may be responsible for at least one of the vulnerable conditions. Therefore, it is tremendously difficult to assign a percentage of the blame on any single party especially where the absence of any one condition may result in no failure.

Aquatherm had claimed that standard pipe clamps could be used with loosely specified modifications. In practice the pipes are sized in the Metric system and the clamps were sized in the Imperial measurement system. Further, the materiel is soft so there was little feedback for the mechanics accustomed to using a torque wrench. Often we’ll find the failed piece deformed inside the clamp. Is the contractor to blame or Aquatherm?

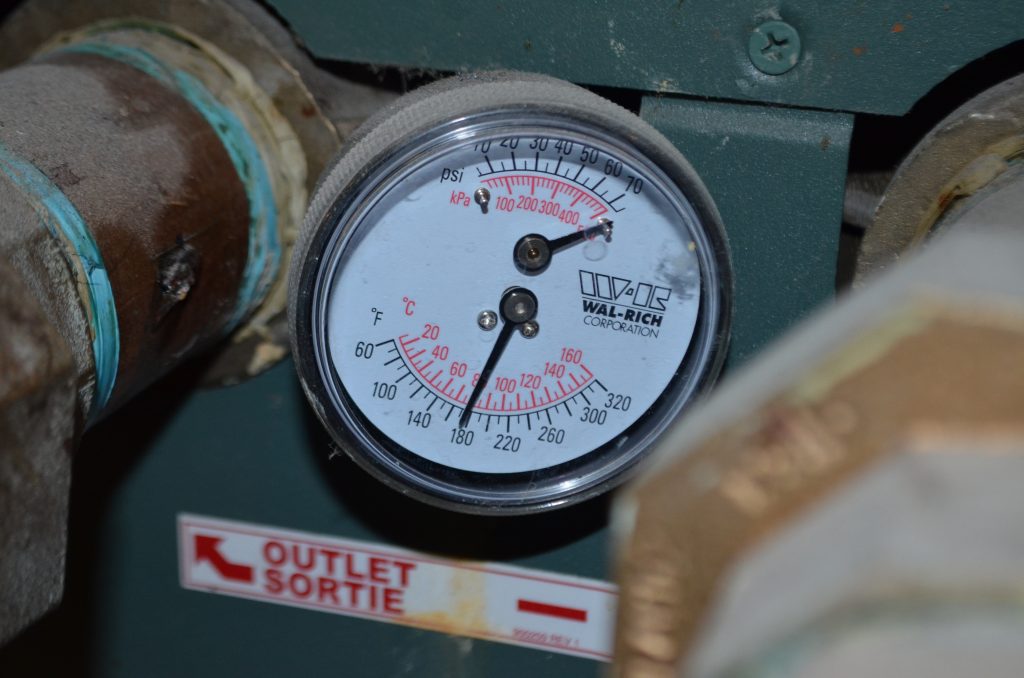

In another case, Aquatherm specified strict temperature and pressure limitations. In the real world, we found two boilers set up incorrectly causing occasional fluctuations beyond the temperature limits – normally not a problem with most other piping systems.

In another case, the boilers had CuNi (Copper/Nickel) heat exchangers that, if not correctly installed or maintained, may be a source of copper ionization. How is the owner / HVAC contractor to know about these details?

In another case, the boilers had CuNi (Copper/Nickel) heat exchangers that, if not correctly installed or maintained, may be a source of copper ionization. How is the owner / HVAC contractor to know about these details?

One of the advantages of Aquatherm is that it can be run at a much faster flow speed than other pipes. If you run water too fast in a system mixed with copper, the turbulence can erode the copper releasing ions to the water system, which can then attack the Aquatherm. Most of the retrofits will have mixed systems in one form or another. Whose responsibility is it to manage mixed systems?

I have been contacted by attorneys on both sides of more than one PPR lawsuit. Most lawyers are looking for a sharp knife to cut their client free from culpability. When I share my thoughts on the topic, based on real-life experience, I’m rarely called back. The last thing they want to hear is that there is plenty of blame to go around. I believe that an inherent bias is baked-in, leading to closed settlements.

I have been contacted by attorneys on both sides of more than one PPR lawsuit. Most lawyers are looking for a sharp knife to cut their client free from culpability. When I share my thoughts on the topic, based on real-life experience, I’m rarely called back. The last thing they want to hear is that there is plenty of blame to go around. I believe that an inherent bias is baked-in, leading to closed settlements.

So, Why DO Aquatherm Pipes Fail?

The answer is simple. Information needs to flow to the industry without fear of repercussion so that owners and operators and installers can mitigate the risk. Most piping materials seem to go through a period of failures until the industry can see how they actually perform over the long term. PolyButylene, CPVC, and PEX have all had their time in the hot-seat. Polypropylene, in my opinion, holds great promise in some applications. Few people want to talk about the details and court settlements are often sealed, so the public and the industry are uninformed.

Instead of learning from mistakes, a new game plays out anew for every instance of failure. This is counterproductive. What really needs to happen is that each of the parties need to fess up, mitigate the failures, and then share information with everyone else so that the problems can be ironed out as soon as possible and this innovative material can achieve its potential.